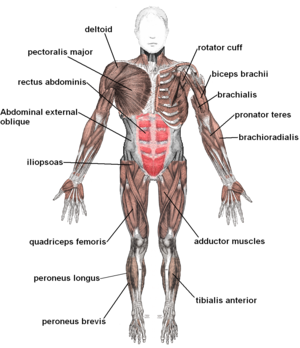

Muscles help pump blood back to the heart to be re-oxygenated. Standing up for micro-breaks is a key part of this. Photo credit: Wikipedia)

The Physiological Rationale for Micro-breaks; Why all OPC Consultants tell employees to take short micro-breaks in the office

Static muscle effort significantly inhibits blood flow, which may lead to musculoskeletal injury (MSI), whereas dynamic muscle efforts, which involve the alternation of tension and relaxation, allow for sufficient blood flow to the muscles.

All of Optimal Performance Consultants (OPC) therefore recommend to all employees we work with in Canada and the US to take micro-breaks during static muscle activity which includes working at the computer, sitting in meeting rooms. These micro-breaks immediately changes the muscle effort from static to dynamic.

The chart above (Grandjean, E and Rodgers, S) illustrate the available and required blood flow and lymph flow (the clear fluid part of the bloodstream carried in the lymphatic system) during rest, dynamic, and static efforts. The trick in a computerized office or meeting space and even on an airplane during travel is to have external feedback or prompts for employees to take a micro-break whenever the muscle has been held contracted continuously for 60 seconds. Or think about how your hand often hovers above your mouse as you consider whether to point and click on an item on your screen; this is a prime example of static loads at your forearm.

Micro breaks are 1–2 second changes in muscle tension approximately every 20-30 minutes where we recommend employees move away from their desks and change their task or stand & stretch. During use, muscles contract around the blood vessels inhibiting blood flow. If tension is maintained without interruption (static effort), blood as well as lymph flow is inhibited at a time when more flow is required. Chronic static loads can result in injury and discomfort, which is referred to early on as Musculoskeletal Disorders (MSD). This Disorder can further lead to an actual Musculoskeletal Injury or MSI at any of the soft tissues of the musculoskeletal system.

When effort is dynamic—the alternation of tension and relaxation—blood and lymph are pumped through the muscles and health is maintained. A common example of dynamic effort is standing and walking: we can stand or walk for extended periods of time without discomfort (resting or dynamic effort) because our blood/lymph flow matches our effort. However, if employees hold their shoulders statically by not supporting their arms onto the armrests of the chair (static effort), they will experience discomfort quickly because static effort demands similar blood/lymph flow as the dynamic. The chart above is a simple illustration of the body’s need for blood and lymph flow during activities.

Taking micro-breaks immediately after static muscle activity, such as working at the computer, changes the effort from static to dynamic right away.

Many employees whom we have worked in Canada and the US report a significant increase in energy & with a decrease in discomfort when they take micro-breaks after keying & mousing or in the middle of a meeting.

The science behind the use of micro-breaks right after a static load has occurred is very clear. Now it is up to employees to think about how they work in order to alter their work behaviours to maintain a healthy musculoskeletal system.

References

Grandjean, E. (1987). Ergonomics in computerized offices. New York: Taylor and Francis.

Peper, E., & Gibney, K. H. (2000). Healthy computing with muscle biofeedback: A practical manual for preventing repetitive motion injury.

Suzanne H. Rodgers, A functional job evaluation technique, in Ergonomics, edited by J.S. Moore and A. Garg, Occupational Medicine: State of the Art Reviews. 7(4):679-711,1992

Rhomert, Work to Recovery Calculations and Recovery Time Charts; see photo